By Rusty Chinnis

I consider myself extremely lucky to have spent the last 40-plus years on an island in an area celebrated as the Suncoast. As an ardent angler, I’ve explored the bays, estuaries, islands and Gulf and feel incredibly blessed for the opportunities I’ve had. Like other anglers, I share the desire to give back, to work to protect this incredibly rich and diverse habitat, after experiencing we humans’ effects on its health over time.

When I arrived here in 1981, the waters of the Suncoast were beginning to recover from decades of unregulated dredge-and-fill projects, stormwater runoff, overfishing and inadequate sewage systems. Over four decades I saw bag and size limits created to protect fish stocks and watched as waters begin to recover as insults were addressed. Seagrass was growing back and there was cause for hope and celebration. Red tides and algae blooms still occurred, and nitrogen levels increased, but we seemed to be on a hopeful track.

Unfortunately, all that was so laboriously gained over half a century has been lost in just the last six years. Seagrass beds disappeared, lyngbya algae blooms, late summer occurrences since the 1980s, exploded in early spring and blanketed the already stressed grass beds and left shorelines lined in anoxic milky-white water. Populations of some fish species plummeted and businesses suffered.

One of the advantages anglers have living in and fishing an area over time is the ability (given that our eyes and minds are open) to gain insight into the seemingly inexorable changes that occur around us. As I’ve worked with like-minded individuals to protect mangroves, fish stocks and the waters of our bays and Gulf, I always wondered why harmful algae blooms, a/k/a red tides, were reported by the Spaniards in the 16th and 17th centuries, long before overpopulation threw the system off balance. The answer to that question came to me as I read the accounts of those same Spaniards, Cuban fishermen and indigenous peoples in Jack Davis’ Pulitzer Prize-winning book “The Gulf, The Making of an American Sea.” In those pages, I learned about accounts relating to instances of the skies turning dark as thousands of seabirds passed overhead on a cloudless day, of fish schools so thick that it wasn’t much of an overstatement that you could walk their backs across broad stretches of the inland bays.

Suddenly it became clear to me (caveat, I’m no scientist) that the same red tides that polluters discount by saying “it’s natural” (like cancer’s normal is my retort) may have been nature’s way of attempting to keep the waters balanced. Before man left his scars on the ecosystem, the explosion of life was kept in check by this organism that is triggered to bloom by excess nitrogen. It dawned on me that harmful algae blooms may function like forest fires in a natural system. Now the same marker nitrogen, now produced by human activity, triggers longer and more intense outbreaks that increase as the human population grows.

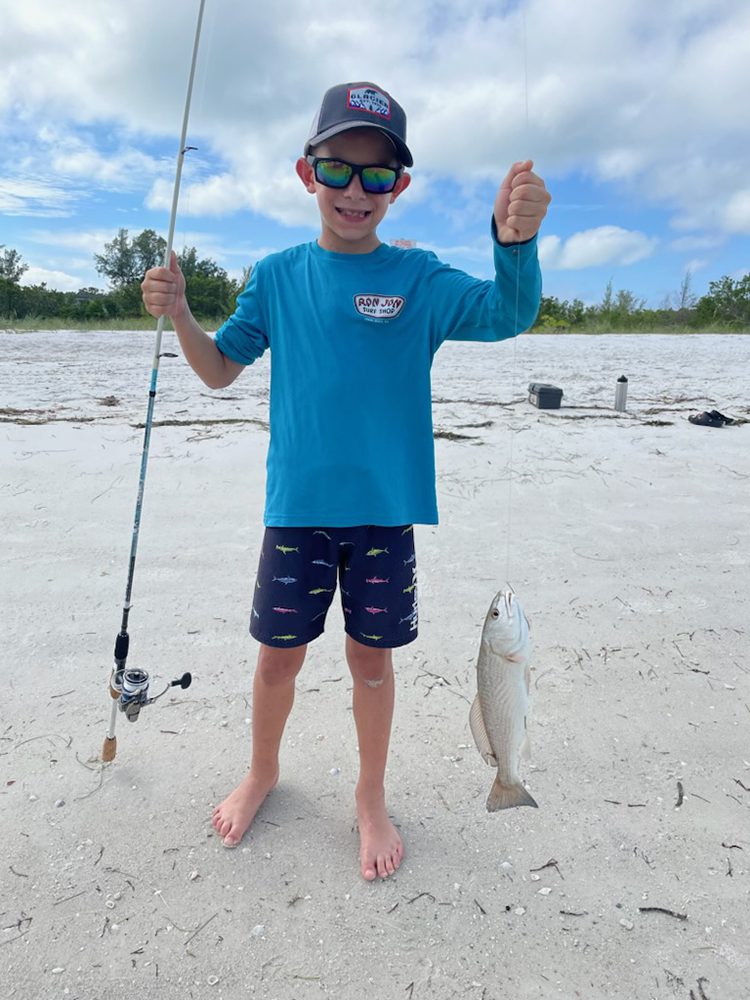

Every time I’m at the beach and see young children splashing in the surf with gleeful enthusiasm and fishing the local piers, I have to wonder what kind of world will we leave these kids? My experiences, the lessons I’ve learned, and the camaraderie of friends on the Suncoast have been an incentive to give back for all we’ve been given. To be sure in these strange and uncertain times the progress attained by these efforts can verge on being depressing. That’s why I have to constantly remind myself of the words of the Dalai Lama, “If you work to save the world and the world is lost, no regrets.”