This article originally appeared in Reel Time in 2018. It’s republished here, with revisions, because I think the message it imparts has never been more relevant. Respect and action to protect this amazing marine biosphere that surrounds us have never been more necessary or compelling. This formative work of history made me see this land where I have lived for over four decades with new eyes. I wanted to share it again.

“The real voyage of discovery consists not of seeking new lands but of seeing with new eyes.”

Marcel Proust

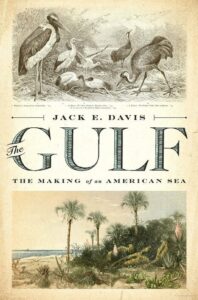

As I read Jack Davis’s new book, “Gulf, The Making of An American Sea,” the quote by the seminal French novelist Marcel Proust came to mind.

Having lived on Florida’s Gulf Coast for close to 40 years and been privileged to explore its rivers, bays and estuaries, I have been captivated by its beauty and the fish that swim in its waters. Being immersed in this wonderland had to some extent clouded my sensibilities by making the place so familiar. Reading “Gulf,” however, shined a clear light on what we have, what we’ve lost and the importance of protecting its treasures for future generations.

Davis’ book begins 150 million years ago when the geological forces of an evolving earth began shaping the Gulf we know today. In part one, he introduces us to the Calusa, in Florida, and the Karankawa, who inhabited present-day Texas, as the original inhabitants of “one of the largest estuarine regions in the world, encompassing more than 200 estuaries and occupying nearly 8 million acres.”

Davis’ book begins 150 million years ago when the geological forces of an evolving earth began shaping the Gulf we know today. In part one, he introduces us to the Calusa, in Florida, and the Karankawa, who inhabited present-day Texas, as the original inhabitants of “one of the largest estuarine regions in the world, encompassing more than 200 estuaries and occupying nearly 8 million acres.”

The book then traces the impact of the early Spanish explorers who led the way for the French and British. Descriptions of the vast schools of fish and flocks of birds that would “blacken the sky” hint at the incredible diversity and density of marine and other wildlife that once inhabited the Gulf and its estuaries.

In a later chapter entitled “The Wild Fish That Tamed the Coast,” Davis recounts how the tarpon, not warm weather and white-sand beaches, brought the first tourists to Florida. The records are unclear about who took the first tarpon with a rod and reel. Some say it was New York Architect William Halsey Wood, fishing in Pine Island Sound in 1885. Others claim it was Anthony Weston Dimock at the mouth of the Homosassa River.

Whoever the angler was, that first tarpon was the impetus that introduced wealthy adventurers, artists and, indirectly, waves of other tourists to the Gulf Coast.

Subsequent chapters show the influx of humans into the Gulf region beginning a period of intense exploitation in the 1800s that continues to this day. Davis recounts records of tourist passengers on boats in the Ocklawaha River that shot birds and other wildlife indiscriminately for sport. At the same time, the plume trade was responsible for killing huge numbers of birds Gulf-wide. In 1902, one trade house reported an inventory of 50,000 ounces of feathers. At about that time, ornithologist Frank Chapman spent two afternoons walking Manhattan’s retail district counting 542 feathered hats representing 174 species of birds. During this same period, the harvesting of eggs from seabird nests exacerbated the decline of the once vast flocks. Davis paints a picture with his words that graphically illustrates the effects of this dark period.

Fortunately, an outcry from conservationists and birders shed light on this gloomy picture, revealing it to the world. As a result, bird sanctuaries were set aside by an executive order from President Theodore Roosevelt, and chapters of the National Audubon Society were born, including the Florida chapter in 1900. During that period, Roosevelt created 51 bird refuges, including Passage Key at the mouth of Tampa Bay.

The history of the Gulf unfolding in this book shows that the exploitation moved from birds to oil and then chemicals that devastated the coastal estuaries of Louisiana and Mississippi. Davis recounts the effects of pulp mills and oil spills before the rush of development that included massive dredge-and-fill operations. This rush to the Gulf’s coastal areas scoured seagrasses from bay bottoms and leveled thousands of acres of marshes and mangroves to create islands and communities, including those we know today as Marco Island, Cape Coral, Bird Key and Tierra Verde.

While much of the book centers on the degradation of the Gulf and its bays, estuaries and barrier islands, it also points out the resilience of this American Sea and serves as a cautionary tale about the importance of protecting, preserving and enhancing it today.

Davis’ excellent book reopened my eyes to the paradise that still surrounds us.